Industry Fees & Taxation

Challenges and what countries are doing about them

Taxation in the Digitalized Economy

Digitalization of our economic activities and pervasive new technologies have been and are a key driver of change and bring significant benefits and opportunities. They are also disrupting the world as we know it, and have a profound reach into everyday life. They affect how we live, work, communicate and interact, connect, consume and produce, how we create knowledge, how we function and act as a society, and so much more. According to CISCO, the global internet community consisted of 3 billion users in 2015, with 16.3 billion devices connected to the internet globally, which CISCO expects to increase to 4.1 billion users and 26.3 billion devices by 2020. New businesses are created that range from being entirely digital, relying on intangible assets and user participation, no longer requiring physical assets such as offices or sales outlets or large numbers of employees, to businesses that have digitalized some of their aspects and functions. For example, Airbnb, the world’s largest accommodation provider, owns no real estate and Uber, the world’s largest taxi company, owns no vehicles. Alibaba, the most valuable retailer, has no inventory, and Facebook, the world’s most popular media owner, creates no content. While we used to look at these companies and their activities as distinct from traditional and domestic businesses and economic activities, it is increasingly difficult to do so. This is particularly so for taxation purposes. The OECD in its 2015 Action 1 Report acknowledges that it would be difficult, if not impossible, to ‘ring-fence’ the digital economy from the rest of the economy for tax purposes because of the increasingly pervasive nature of digitalization. Instead, it considers “digitalization as a transformative process affecting all sectors brought by advances in ICT”. Thereby the “digital economy” is becoming the economy itself.

In this context of convergence, governments are increasingly concerned with tax revenue losses arising from multinational tax planning by MNEs that result in base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) and other, broader tax challenges. Tax revenue losses resulting from BEPS have been conservatively estimated by the OECD to amount to US$100-240 billion per annum globally. BEPS is not a new problem – MNEs have always pursued tax minimization strategies – but certain features of the digitalized economy exacerbate the issues. These features have created a mismatch or disconnect between where profits are made, taxes are paid and where value is created. Also, this mismatch has repercussions at the local level, and can lead to distortions along the digital value chain and across different economic sectors. Therefore, the international community such as the OECD and leading jurisdictions such as the EU are examining how the international tax framework is being challenged by changes in how global businesses are managed and structured and are undertaking efforts to identify - for the long term - how the international taxation framework can be adjusted to cater better to an increasingly digitalized world. In the short term pending an international solution, individual countries are moving unilaterally, such as the UK, India or Slovakia, but also the EU, putting forward and implementing proposals to ensure that digital businesses pay tax that reflects the value they derive from users located in consumption countries. Such measures include digital services taxes, digital transaction taxes, digital platform taxes, equalization levies and changes to concepts of permanent physical establishment.

The article briefly examines the key features of the digitalized economy and the key issues that arise from them for taxation under current international tax rules, their repercussions at the local level, and summarizes what countries are doing to address the issues identified.

The way in which businesses carry out their global activities has been fundamentally changed by digitalization and technological advancement. With borderless digital infrastructures, such as the Internet, new business models have emerged that facilitate the creation of global digital companies that are much more flexible and have instant global reach. These digital companies create economic value by relying on platform economics (e.g. network effects, economies of scale and market power), intangible assets and user-generated data, with suppliers, consumers and marketplaces often located in different tax jurisdictions. Where once companies had a physical establishment in the country of consumption, digital companies / platforms now have greater flexibility over where they locate their business activities with the ability of connecting employees in different countries through their online platforms and accessing different geographic markets with ease from a limited number of remote locations, without the need for a material local presence. Moreover, for many digital businesses that operate in markets through an online platform, the users of the platform (which may or may not be identical to a business’s consumers) play a more integral role in the pursuit of revenue and create material value for a business through their sustained engagement and active participation. In addition, new multi-sided business models have emerged that are far more flexible and allow for much greater reach. These business models used by e.g. over-the-top businesses enable much easier connection of geographically distinct user groups to maximize value on each side, where for example, resources designed to collect data can be located near individual users, whereas the infrastructure necessary to sell this data to paying customers can be located elsewhere.

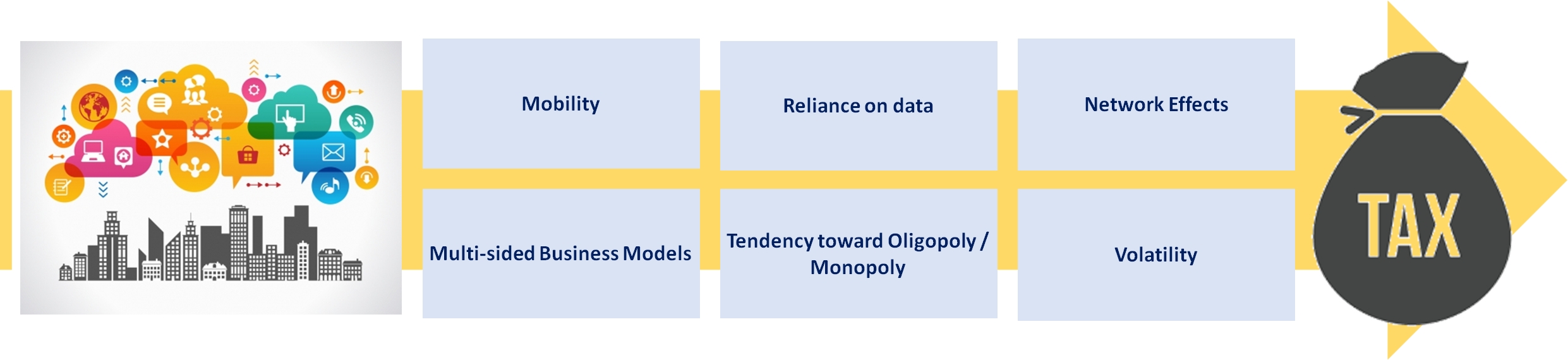

The OECD within its Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project (“BEPS”) has identified several key features of the digitalized economy that are potentially relevant from a tax perspective. These include mobility, reliance on data, network effects, use of multi-sided business models, tendency towards monopoly or oligopoly and volatility. Mobility has significantly increased as it relates to intangible, users and customers, as well as business functions. Digital companies rely on and invest heavily in the exploitation and development of intangibles (e.g. software), which are a core contributor to value creation and economic growth. The OECD Report 2015 finds that under existing tax rules, the rights to those intangibles can often be easily assigned and transferred among associated enterprises, with the result that the legal ownership of the assets may be separated from the activities that resulted in the development of those assets. In addition, digital companies also serve a much more mobile user- and customer base than traditional businesses.

INFOBOX on BEPS – what does it mean, and why it is relevant to the debate?

Base erosion and profit shifting concerns (BEPS) are raised by situations in which taxable income can be artificially segregated from the activities that generate it, or in the case of VAT, situations in which no or an inappropriately low amount of tax is collected on remote digital supplies to exempt businesses or multi-location enterprises that are engaged in exempt activities. These situations undermine the integrity of the tax system and potentially increase the difficulty of reaching revenue goals. In addition, when certain taxpayers are able to shift taxable income away from the jurisdiction in which income producing activities are conducted, other taxpayers may ultimately bear a greater share of the burden. BEPS activities also distort competition, as corporations operating only in domestic markets or refraining from BEPS activities may face a competitive disadvantage relative to MNEs that are able to avoid or reduce tax by shifting their profits across borders.

The February 2013 OECD report “Addressing Base Erosion and Profit Shifting” (February BEPS Report) identifies a number of coordinated strategies associated with BEPS in the context of direct taxation, which can often be broken down into four elements:

- Minimization of taxation in the market country by avoiding a taxable presence, or in the case of a taxable presence, either by shifting gross profits via trading structures or by reducing net profit by maximizing deductions at the level of the payer;

- Low or no withholding tax at source;

- Low or no taxation at the level of the recipient (which can be achieved via low-tax jurisdictions, preferential regimes, or hybrid mismatch arrangements) with entitlement to substantial non- routine profits often built-up via intra-group arrangements; and

- No current taxation of the low-tax profits at the level of the ultimate parent.

BEPS is relevant in the context of a digitalized economy, as certain features of the digitalized economy exacerbate the issues of BEPS and create other, broader tax challenges.

The mobility of users and customers relates to users’ ability to purchase services in one location and consume these services in other locations, when e.g. travelling. In a digitalized economy, where the location of a user may be concealed, difficulties can arise to determine the location of an ultimate sale which has repercussions for e.g. VAT collection. Moreover, entire business functions can easily be managed over long distances from one central location and with a minimum need of personnel present, where operations are carried out in one location and suppliers and customers are located in another location, enabled through improved telecommunications, information management software, and personal computing. This has improved the capacity of businesses to manage their global operations on an integrated basis and adopt global business models that centralize functions at a regional or global level, rather than at a country-by-country level. This enables individual group companies to exercise their functions within a framework of group policies and strategies set by the group as a whole and monitored centrally. This way, companies can achieve “scale without mass”, which has also enabled SMEs to become “micro-multinationals” that operate and have personnel in multiple countries and continents.

Figure 1: Key Features of Digitalization potentially relevant for taxation

Digital companies also heavily rely on user generated data and user participation in their value creation. This has been facilitated by an increase in computing power and storage capacity and a decrease in data storage cost. This, in turn, has greatly increased the ability to collect, store, and analyze “big data” at a greater distance and in greater quantities. Whereas companies have always relied on data regarding customer preferences to improve products and services, the scale and complexity of data collection, storage and processing is exponentially greater in the digitalized economy. The OECD 2015 report highlights that traditional data collection for utility companies was limited to yearly measurement, coupled with random samplings throughout the year. With smart metering on the other hand, the measurement rate could be increased to 15 minute samples, which would equate to a 35 000 time increase in the amount of data collected. This capacity to collect and analyze data will continue to rapidly increase as the number of sensors embedded in devices that are networked to computing resources increases.

Network effects are also a key component of new digital business models as they relate to user participation, integration and synergies: a product or service gains additional value as more people use it, e.g. social networking, instant messaging, chat services, or a widely-adopted operating system and corresponding software written for it, resulting in a better user experience. Network effects are positive externalities, where the welfare of a person is improved by the actions of other persons, without explicit compensation. Leveraging these network effects, multi-sided business models have emerged as another key feature of the digitalized economy, in which the two sides of the market may be in different jurisdictions. A multi-sided business model is based on a market in which multiple distinct groups of persons interact through an intermediary or platform, and the decisions of each group of persons affects the outcome for the other groups of persons through a positive or negative externality. In a multi-sided business model, the prices charged to the members of each group reflect the effects of these externalities. If the activities of one side create a positive externality for another side (e.g. more clicks by users on links sponsored by advertisers), then the prices to that other side can be increased.

It should be noted that multi-sided business models are more prevalent in a cross-border context and feature two specific characteristics: flexibility and reach. Digital businesses are able to flexibly use resources (content, user data, executable code), that don’t expire due to their ability to be stored. These resources can create value for a company long after they have been produced and can be dynamically adapted based on evolving technology. They can also be used to enhance the value to one side of a market of the participation of the other side of the market. Moreover, digital businesses such as over-the-top platforms have much greater reach through the ability to more easily connect two sides that are located far from one another to maximize value on each side.

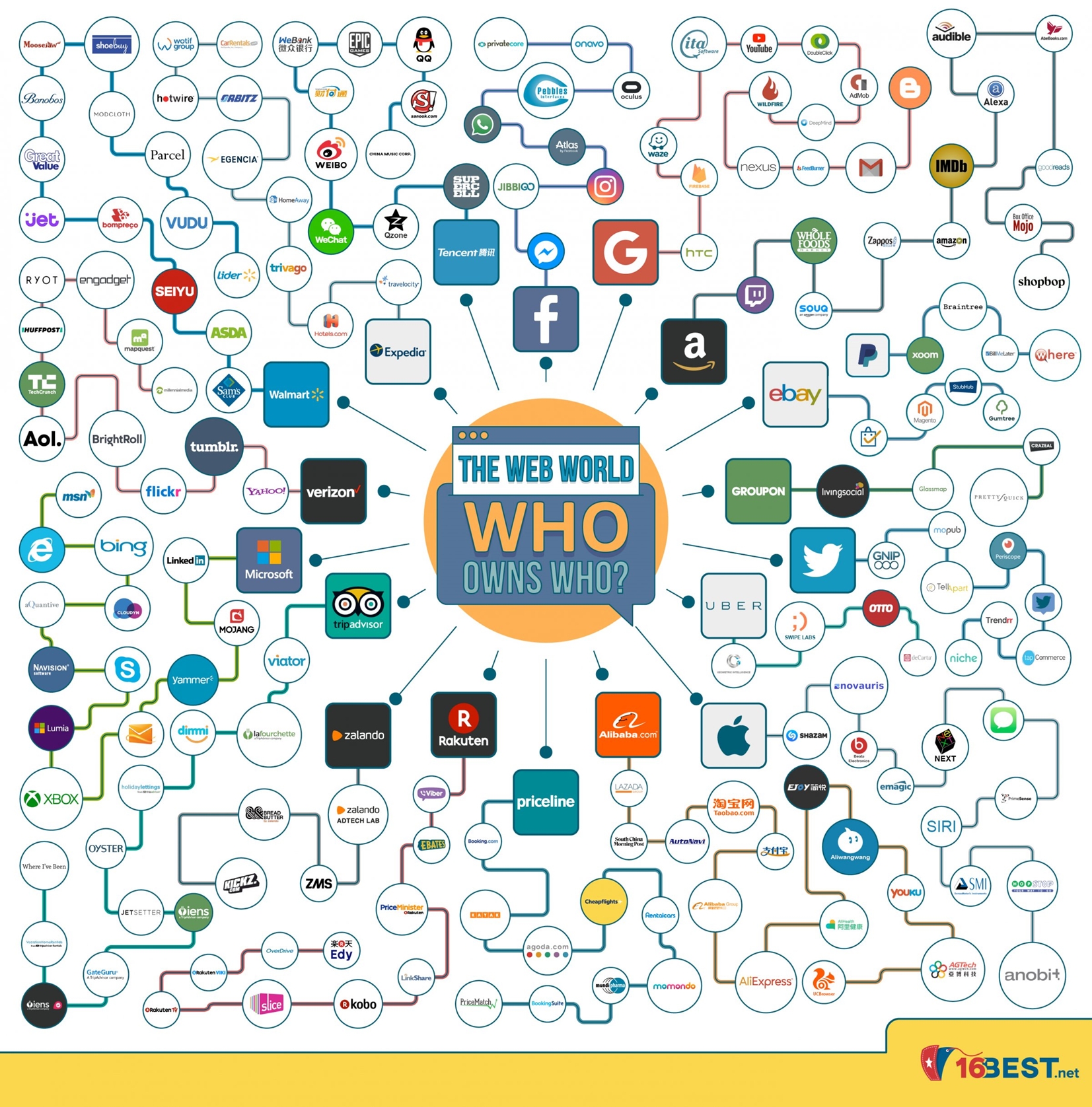

Taken together, the OECD 2015 Report finds that the prevalence of network effects and multi-sided business models that are often cross-border, coupled with reliance on intangible assets such as IP have a tendency toward creating monopolistic or oligopolistic structures. Where network effects are combined with low incremental costs, a company can quickly achieve a dominant position. The effect is exacerbated, where a company holds a patent or other intellectual property rights, so that is can seamlessly innovate. The OECD highlights that the impact of these network effects tends to lead to such structures, for example, where companies provide a platform or market in which users on one side of the market prefer to use only a single provider, so that value to those users is enhanced when a single standard is chosen, and the price that can be charged to the other side is enhanced because the platform becomes the only means of access to those users. Moreover, given low barriers to entry for Internet-based businesses due to progress in miniaturization and a downward trend in the cost of computing power, coupled with rapid technological development, digital markets can be volatile. While volatility could provide a check on monopolistic structures, it is strategically counteracted by long-term successful digital companies through vertical and horizontal integration and acquisition of start-ups with innovative ideas (e.g. Facebook, who bought WhatsApp and Instagram to complement its social networking site). This enables digital companies to stay relevant, launching new features and new products, and continually evaluating and modifying business models in order to leverage their market position and maintain dominance in the market. Figure 2 shows the Web World and Who owns Who.

Figure 2: The Web World and Who owns Who 2018

These new features of mobility, reliance on data, network effects, use of multi-sided business models, tendency towards monopoly or oligopoly and volatility as described above, are said to enable economic actors to operate in ways that avoid, remove, or significantly reduce, their tax liability within traditional tax bases. They may also generate base erosion and profit shifting concerns in relation to both direct and indirect taxes. The OECD 2015 Report states, for example, that the importance of intangibles in the context of the digitalized economy, combined with the mobility of intangibles for tax purposes under existing tax rules, may generate substantial base erosion and profit shifting opportunities in the area of direct taxes. It also highlights that the mobility of users may create substantial challenges and risks in the context of the imposition of value added tax (VAT). Furthermore, the ability to centralize infrastructure at a distance from a market jurisdiction and conduct substantial sales into that market from a remote location, combined with the increasing ability to conduct substantial activity with minimal use of personnel, may generate potential opportunities to achieve base erosion and profit shifting by fragmenting physical operations to avoid taxation.

So, in how far do these features affect taxation? Why do these features create issues with current international tax rules and make governments worry about losing corporate tax revenue, collecting VAT, or broader issues such as their effect on local competition or the creation of asymmetries vis-à-vis other economic sectors? To understand why the features as identified above create problems for the current international tax framework, we need to understand what the international tax framework is based on and designed to do.

Cross-border taxation issues are regulated using domestic tax law, tax treaties and other international law instruments, such as international tax rules and standards. Whilst the classic example is a tax treaty that resolves double-taxation issues, there are also rules and standards relating to matters such as transfer pricing, dispute resolution mechanisms and tax information exchange. The OECD’s Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital serves as a basis for more than 3500 bilateral tax treaties, along with the United Nations Model Double Taxation Convention between Developed and Developing Countries. The OECD has also developed Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations. Furthermore, the Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes (Global Forum) is a framework where OECD and non-OECD member jurisdictions are working together to promote standards in the international exchange of tax information between tax administration bodies.

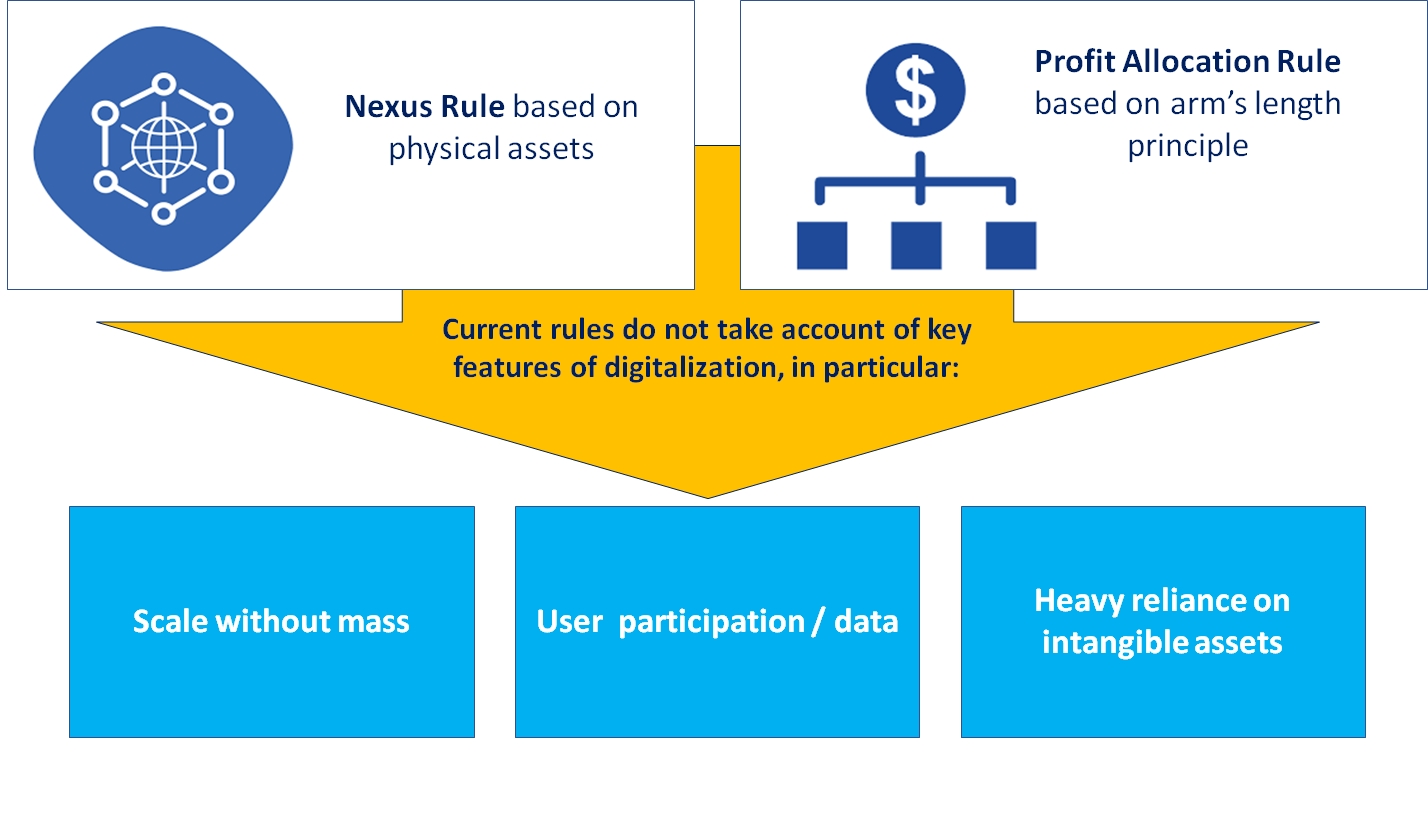

The current international tax framework was developed in the 1920s and determines how business profits from cross-border activities are taxed. It allocates taxing rights based on the location of physical assets, capital and labour, the source of income and the residence of taxpayers. It is based on two key concepts, namely (1) the nexus rule to determine jurisdiction to tax a non-resident enterprise and, (2) the profit allocation rule, based on the arm’s length principle. It does not take account of the extent to which businesses have become globalized and digitalized. Because digitalization and its new business models have created a mismatch between where profits are made and where value is created, questions are arising with regards to the relevance and effectiveness of these two key concepts. To examine the question of why the two key concepts of nexus and profit allocation may no longer hold in the digitalized economy, we need to first understand how highly digitalized businesses are taxed.

Figure 3: Key principles of the International Tax Framework and its “digital” shortfalls

In most jurisdictions, highly digitalized companies are normally subject to the market country’s domestic tax framework, just like traditional businesses operating in the consumption country. Their consumption country sourced profits will be subject to the consumption country’s domestic income tax, and the goods and services consumed by the consumption country’s consumers will generally be subject to VAT. However, problems arise because many foreign-based, highly digitalized companies have relatively small consumption country sourced profits, because the majority of their profit-generating assets and labour are located outside the consumption country. Moreover, the development of new digital products or means of delivering services creates uncertainties in relation to the proper characterization of payments made in the context of new business models, particularly in relation to cloud computing. Also, companies gather and use information across borders to an unprecedented degree, which raises the issues of how to attribute value created from the generation of data through digital products and services, and of how to characterize for tax purposes a person or entity’s supply of data in a transaction (e.g., as a free supply of a good, as a barter transaction, or in some other way). Further, the fact that users of a participative networked platform contribute user-generated content, with the result that the value of the platform to existing users is enhanced as new users join and contribute, may raise other challenges.

As identified above, a common characteristic of most digital businesses is the ability to access a market via technological means without necessarily having a physical presence or a significant number of employees in that market, i.e. they have the ability to achieve “scale without mass”. Because the current international tax framework relies on nexus based on physical assets, a mismatch is created between “consumption” and “production” countries, as profits are taxed where digital companies hold their physical assets, but not where they generate most of their value through e.g. user participation and data generated through digital services and products. Moreover, digital businesses often rely heavily on highly mobile, intangible assets. These assets, such as algorithms, can be located anywhere in the world, and usually only require a network to be established for them to be accessed. As a result, a digital business may have a significant economic presence in one jurisdiction, while the majority of its profit-generating assets and labour can be located in a different jurisdiction. In this way, under the international tax framework and the consumption country’s corporate income tax systems, only a relatively small amount of the global profits of a highly digitalized multinational company may be sourced in the consumption country. It should be noted that a multinational enterprise’s capacity to have a significant economic presence in the consumption country, but pay a small amount of tax there is not a new challenge. For decades, foreign businesses in a range of sectors of the traditional economy have operated business models where the majority of profit-generating assets and labour have been located offshore. However, increasing digitalization and increasingly mobile intangible assets intensify this challenge, particularly in sectors of the economy most affected by digital disruption.

Taxation is essentially about managing the interests of governments, industry stakeholders and consumers, which often lie at opposite ends of the spectrum: governments need to ensure that they have enough revenue to finance their expenditures for public services; businesses need to make sure they are incentivized and have sufficient funds available for investment, and consumers must have enough income to consume. It is therefore essential to understand what the implications are from addressing those interests through taxation.

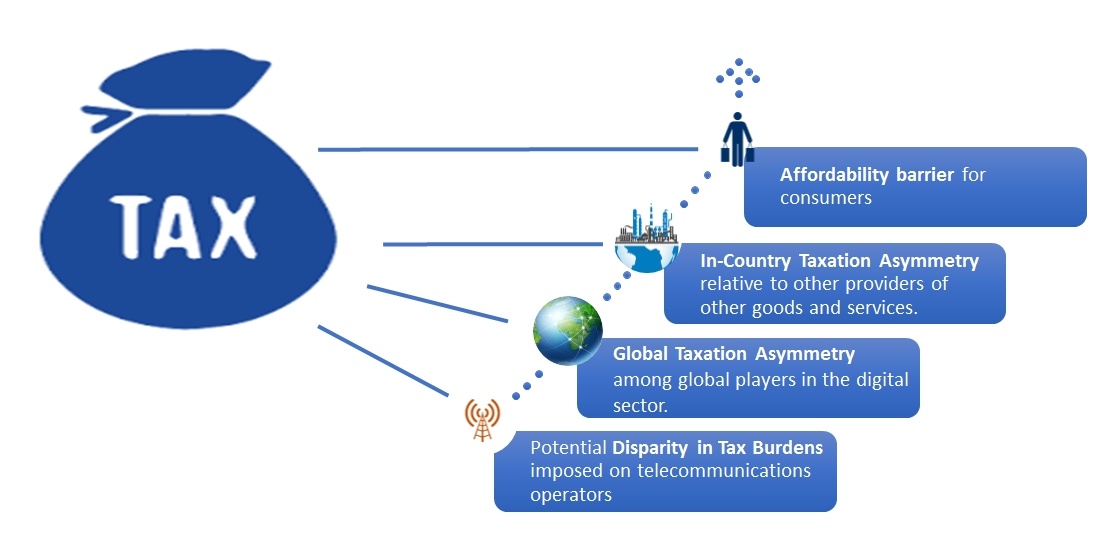

Figure 4: Distortive Effects of taxes in the Digital Ecosystem

Taxes can bring these interests into imbalance when they affect the choices of stakeholders made over and above what would happen in the absence of them. Therefore, in principle, taxation should attempt to be neutral and equitable across all sectors of the economy. At the global level, this principle should also hold and it should be ensured that the interests of “consumption” and “residence” countries are managed in a neutrally balanced manner. Ensuring this principle in the digital economy, however, is a lot more complex than it used to be in the analogue world and has created new and more systemic challenges for tax policymakers and tax administrators. As a first step, however, the international tax framework must be in line with domestic corporate income tax systems, which should reflect the changed way of doing business based on the new features of the digitalized economy, to avoid distortive effects at the local and global levels. Figure 4 shows the distortive effects that can arise when tax effects are not neutral and when the international tax framework and domestic tax systems are not aligned.

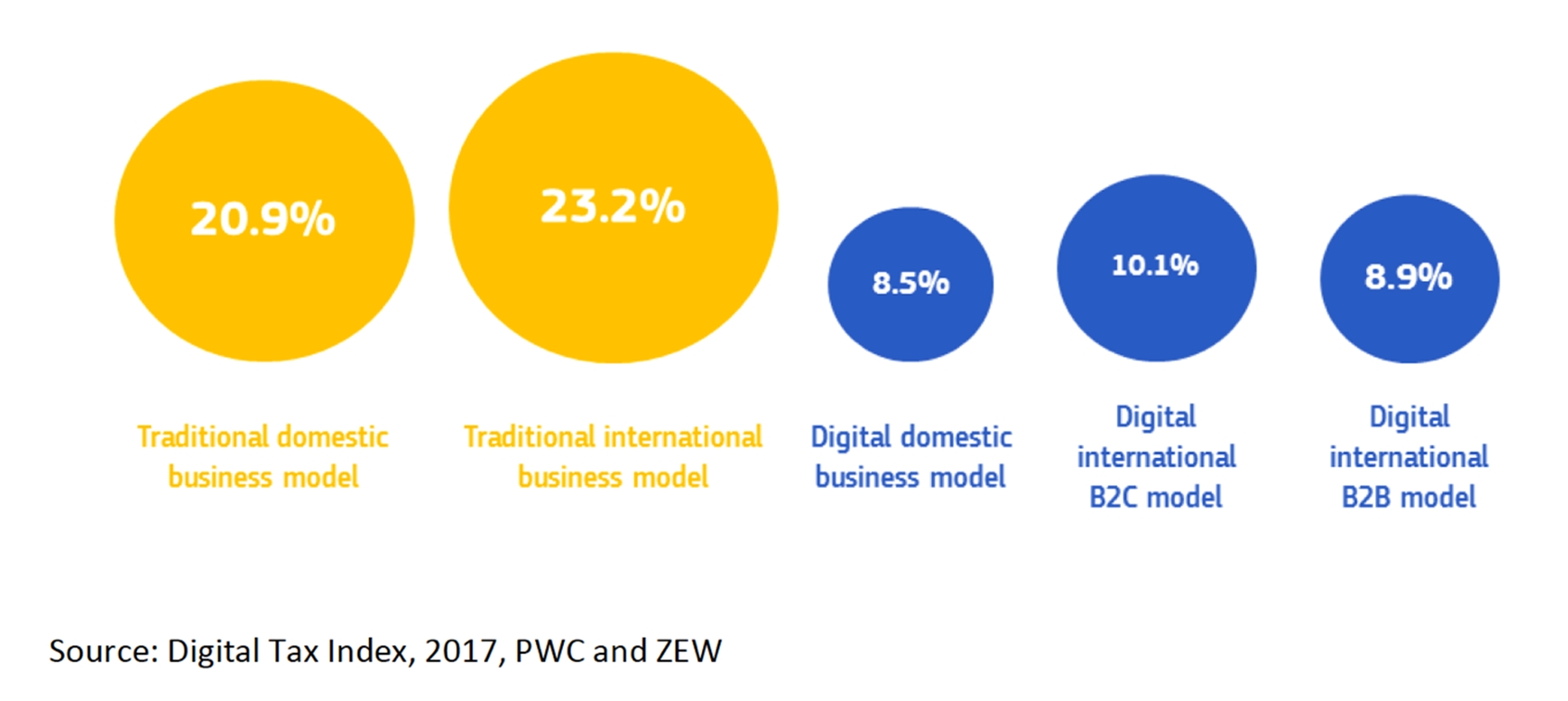

The OECD Interim Report 2018 finds that from a strategic tax policy perspective the uptake of digital technologies may potentially constrain the options available to policymakers in relation to the overall tax mix. For decades, companies have contributed to public expenses via a broad range of taxes in addition to corporate income tax. These taxes include employment taxes, environmental taxes, property and land taxes. These fall to the wayside, with less businesses requiring physical presence and serving markets from remote locations. This, in turn, may increase the pressure on a smaller number of taxpayers to compensate for the related loss of revenues, e.g. increases of taxes and fees imposed on the telecommunications sector vis-à-vis other economic sectors to bridge the revenue gap. This can negatively impact investment incentives and uptake through increased costs. A study by the European Commission found that the average effective tax rate for tech businesses was only between 8.5%-10.1% —less than half of the 23.2% for traditional businesses.

Figure 5: Effective average tax rate in EU 28

To address the high-level tax challenges relating to the international tax framework, the OECD and the EU have been working to drive the development of an international solution to digital economy taxation issues, with the focus on “nexus” (namely, addressing the disconnect between tax jurisdiction and the location of value creation by expanding the definition of PE to encompass “digital presence” as determined by the location of a service’s users), and reallocating profits (namely, reallocating taxing rights among the “countries of residence”, the tax havens, and the “countries of consumption” by modifying the formulas for allocating taxable income with the users’ contribution in mind (boosting the share taxable by the countries of consumption)).

Individual countries do not want to wait, pending globally agreed solutions, and are moving forward with short-term gap-stop measures, including the UK, Australia, France, Italy, Slowakia, India, and many others,. Australia is currently consulting on its corporate tax system in the context of the digital economy and is specifically consulting on the questions whether taxing rights should change to reflect user-created value and value associated with intangibles; whether existing profit attribution rules should be changed; whether existing nexus rules for determining which countries have the right to tax foreign resident companies should be changed; and lastly, whether changes can only apply to highly digitalized businesses. The consultation closes on 30 November 2018. While the UK government remains committed to reform of the international corporate tax framework for digital businesses, pending global reform, it is undertaking interim action, to ensure that digital businesses pay tax that reflects the value they derive from UK users. The UK government has therefore announced that it will introduce a Digital Services Tax (DST) from April 2020, which is estimated to raise £1.5 billion over four years. French President Emanuel Macron proposed a new tax on internet companies in April 2018, although without providing any detail. Other examples of unilateral action include Italy, which established a 3% web tax on digital transactions, effective January 1, 2019; Slovakia, which amended its income tax in January 2018 to add a tax on providers of services on digital platforms; Hungary, which proposed an internet tax in October 2017; and India, which introduced an equalization levy on online advertising revenue in 2016 and a revised permanent establishment concept in 2018.

(Source: UK HM Treasury Digital Services Tax fact sheet)

The UK government, pending international efforts, decided to introduce a Digital Service Tax to ensure that the corporate tax system is sustainable and fair across different types of businesses, i.e. that digital businesses pay tax that reflects the value they derive from UK users. The tax will come into effect in April 2020 and will apply only to digital businesses that are profitable and generate at least £500 million a year in global revenues.

- The development of the digital economy has brought significant benefits to all of us, but poses a challenge for the international corporate tax system. The government has set out these challenges in two position papers, published at Autumn Budget 2017, and Spring Statement 2018. They explain the need to reform international tax rules to ensure they reflect the value users create for digital businesses.

- While the government believes that the long-term answer to these challenges is reform of the global tax system – and has been pushing for that to happen internationally – the outcome of that process remains uncertain.

- As a result, the government has decided to act now and will introduce a Digital Services Tax (DST) from April 2020. The DST will raise £1.5 billion over four years and ensure digital businesses pay tax in the UK that reflects the value they derive from UK users.

- The government will continue to lead efforts with its partners in the EU, G20 and OECD to reach international agreement on future reforms to the international corporate tax framework, and will dis-apply the DST when an appropriate international solution is in place.

How will the tax work?

- The DST applies a 2% tax on the revenues of specific digital business models where their revenues are linked the participation of UK users. The tax will apply to: search engines; social media platforms; and online marketplaces. That is because the government considers these business models derive significant value from the participation of their users.

- The DST is not a tax on online sales of goods – as a result it will only apply to revenues earnt from intermediating such sales, not from making the online sale.

- It is also not a generalised tax on online advertising or the collection of data. Businesses will only be taxed on the revenues derived from these services to the extent they are performing one of the in-scope business models, which are the provision of a search engine, social media platform or online marketplace.

- The DST will apply to the revenues that are attributable to in-scope business models whenever they are linked to UK users. This means that, for the purposes of the DST, what matters is the location of the user, not the business. For example:

- if a social media platform generates revenues from targeting adverts at UK users, the government will apply a 2% tax to those revenues

- if a marketplace generates commission by facilitating a transaction between UK users, the government will apply a 2% tax to those revenues

- if a search engine generates revenues from displaying advertising against the result of key search terms inputted by UK users, the government will apply a 2% tax to those revenues

- The DST is intended to be narrowly-targeted, proportionate and ultimately temporary, pending a comprehensive global solution. As such it includes the following features:

- A double threshold – this means businesses will need to generate revenues from in-scope business models of at least £500m globally to become taxable under the DST. The first £25m of relevant UK revenues are also not taxable. This means that small businesses will not be in scope of the tax.

- A safe harbour – this means that businesses can elect to calculate their liability on alternative basis, which will be of benefit to those with very low profit margins. The outcome is that those making losses under this calculation will not have to pay the DST and those with very low profit margins will pay a reduced rate of tax. The government will be consulting on the precise design of the safe harbour which is intended to ensure the DST is proportionate.

- A review clause – this means that the DST will be subject to formal review in 2025 to ensure it is still required following further international discussions. This underlines the government’s commitment to continue seeking a global solution to ultimately replace the DST. In addition, the government will dis-apply the DST if an appropriate international solution is in place prior to 2025.

- The DST will be an allowable expense for UK Corporate Tax purposes under ordinary principles. However, given the DST will not be within the scope of the UK’s double tax treaties, it will not be creditable against UK Corporate Tax.

- Financial and payment services, the provision of online content, sales of software/hardware and television/broadcasting services will not be in scope of the DST. The government will explore with stakeholders during the consultation whether further exemptions should be made.

Next steps

- The government will be issuing a consultation on the design of the DST in the coming weeks. It intends to use this consultation to explore the key questions and challenges concerning the application of the DST, ensure it operates as intended and that it does not place unreasonable burdens on businesses. The DST will then be legislated for in the 2019/2020 Finance Bill, and apply from April 2020.

- Scorecard Year 2018-19 2019-20 2020-21 2021-22 2022-23 2023-24

Yield (£m) N/A +5 +275 +370 +400 +440

In June 2012, more than 110 countries and jurisdictions came together to deal with these and other international tax issues within the OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project. The OECD-G20 BEPS project aimed to respond to identified weaknesses in the international tax framework which were frustrating the principle of aligning profits with value creation and creating opportunities for multinational groups to break that alignment through artificial structures. The process produced a series of multilaterally agreed recommendations and best practice approaches. This included steps to protect the definition of a permanent establishment against avoidance, act against groups shifting taxable profits overseas through interest payments and revise the transfer pricing guidelines to put greater emphasis on real economic activities in determining how profits are allocated between countries. The BEPS project’s “final report,” released in the fall of 2015, fell short of a concrete agreement on measures to address the tax challenges of the digital economy. Since then, talks have continued under the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on BEPS, with the goal of issuing another final report in 2020.

The Inclusive Framework’s interim report, “Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalization,” was released in mid-March 2018 and presented to the G20 finance ministers and central bank governors at their March 19–20 2018 meeting. While none of the fundamental long-term taxation solutions advocated by the “countries of consumption” found their way into the report, the members did agree to review the “nexus” and “profit allocation” rules for determining tax jurisdiction and assigning business income, raising hopes of a decision that would substantially broaden the definition of PE and facilitate the taxation of business profits where they are generated. It was also agreed that any indirect taxes on digital services imposed by individual jurisdictions in the interim should be compliant with existing tax treaties and the rules of the World Trade Organization.

Spotlight: OECD Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) Project, BEPS Package, BEPS Package implementation, the Inclusive Framework on BEPS, Interim Report

(See: http://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/beps-about.htm#background)

Background: With political support of G20 Leaders, the international community has taken joint action to increase transparency and exchange of information in tax matters, and to address weaknesses of the international tax system that create opportunities for BEPS. The internationally agreed standards of transparency and exchange of information in the tax area have put an end to the era of bank secrecy. With over 130 countries and jurisdictions currently participating, the Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes has ensured consistent and effective implementation of international transparency standards since its establishment in 2009. At the same time, the financial crisis and aggressive tax planning by multinational enterprises (MNEs) have put BEPS high on the political agenda. With a conservatively estimated annual revenue loss of USD 100 to 240 billion, the stakes are high for governments around the world. The impact of BEPS on developing countries, as a percentage of tax revenues, is estimated to be even higher than in developed countries.

Development of a comprehensive Action Plan: In September 2013, the G20 Leaders endorsed the ambitious and comprehensive BEPS Action Plan, developed with OECD members. On the basis of this Action Plan, the OECD and G20 countries developed and agreed, on an equal footing, upon a comprehensive package of measures in just two years. These measures were designed to be implemented domestically and through tax treaty provisions in a co-ordinated manner, supported by targeted monitoring and strengthened transparency.

The BEPS Package: The BEPS package provides 15 Actions that equip governments with the domestic and international instruments needed to tackle BEPS. Countries now have the tools to ensure that profits are taxed where economic activities generating the profits are performed and where value is created. These tools also give businesses greater certainty by reducing disputes over the application of international tax rules and standardising compliance requirements.

- The BEPS package consists of reports on 15 actions, and sets out a variety of measures ranging from new minimum standards, the revision of existing standards, as well as common approaches which will facilitate the convergence of national practices, and guidance drawing on best practices.

- In particular, four minimum standards were agreed, to tackle issues in cases where no action by some countries or jurisdictions would have created negative spill overs (including adverse impacts of competitiveness) on others. Their consistent implementation will allow countries to protect their taxable base. Existing standards have also been updated and will be implemented, noting however that not all countries that have participated in the BEPS Project have endorsed the underlying standards on tax treaties or transfer pricing.

- In other areas, such as recommendations on hybrid mismatch arrangements and best practices on interest deductibility, countries and jurisdictions have agreed a general tax policy direction. In these areas, domestic rules are expected to converge through the implementation of the agreed common approaches, thereby still enabling further consideration of whether such measures should become minimum standards. Guidance based on best practices will also support governments intending to act in the areas of mandatory disclosure initiatives or controlled foreign company (CFC) legislation.

Implementing the BEPS Package: The BEPS package was agreed and delivered by OECD members and by G20 economies, and subsequently endorsed by the G20 Leaders Summit in Antalya on 15-16 November 2015. Effective and consistent implementation of the BEPS package requires an inclusive implementation process.

- First, the implementation of the BEPS package into different tax systems should not result in conflicts between domestic systems. Furthermore, the interpretation of the new standards should not lead to increased disputes.

- Finally, it is necessary to ensure a level playing field among countries and jurisdictions in the fight against tax avoidance. Jurisdictions identified as relevant to the work of the Global Forum on Transparency and Information Exchange for Tax Purposes (Global Forum) have already been subject to monitoring and peer review of the implementation of the Global Forum’s standards on transparency and the exchange of information for tax purposes. A similar process is being developed for the implementation of the BEPS package.

- Inclusiveness also means that the implementation process is open to interested countries and jurisdictions. Therefore, the G20 Leaders called in their Communique from November 2015 on the OECD to develop a framework which is open to all interested countries and jurisdictions, including developing countries: “...We, therefore, strongly urge the timely implementation of the project and encourage all countries and jurisdictions, including developing ones, to participate. To monitor the implementation of the BEPS project globally, we call on the OECD to develop an inclusive framework by early 2016 with the involvement of interested non-G20 countries and jurisdictions which commit to implement the BEPS project, including developing economies, on an equal footing.”

The Inclusive Framework on BEPS: The Inclusive Framework on BEPS brings together over 115 countries and jurisdictions to collaborate on the implementation of the OECD/ G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) Package.

- In response to the call of the G20 Leaders, the OECD members and G20 countries have developed an Inclusive Framework which allows interested countries and jurisdictions to work with OECD and G20 members on developing standards on BEPS related issues, and to review and monitor the implementation of the whole BEPS package.

- To join the framework countries and jurisdictions are required to commit to the comprehensive BEPS package and its consistent implementation and to pay an annual BEPS Member fee (reduced when applied to developing countries). However, it is recognized that interested developing countries' timing of implementation may differ from that of other countries and jurisdictions, and that their circumstances should be appropriately addressed in the framework. With a strong political support, the Inclusive Framework is now in place.

- The first meeting of the Inclusive Framework on BEPS was held on 30 June – 1 July 2016 in Kyoto, Japan, and the second one on 26 - 27 January 2017 in Paris, France. To date, 48 countries and jurisdictions have joined the Inclusive Framework with the existing group of 46 countries (including OECD, OECD accession and G20 members), making the total number of countries and jurisdictions participating 94.

- International organisations and regional tax organisations also play an important role in the Inclusive Framework on BEPS, in particular to support the implementation of the BEPS package in developing countries. The African Tax Administration Forum (ATAF), the Centre de rencontres et d'études des dirigeants des administrations fiscales (CREDAF), the Centro Interamericano de Administraciones Tributarias(CIAT) together with other international organisations such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank(WB) and the United Nations (UN) participate in the BEPS work as observers. Furthermore, the IMF, the OECD, the UN and the WBG intensified their co-operation on a wide range of international tax issues through the Platform for Collaboration on Tax, which has been established in April 2016.

Interim Report March 2018: On March 16, 2018, the OECD published its interim report regarding taxation of the digital economy under the title “Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalization”. The OECD interim report, which is the result of a consensus reached between more than 110 member countries, presents an in-depth analysis of the different digital business models and how they create value.

- The challenges of the digitalisation of the economy were identified as one of the main focuses of the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) Action Plan leading to the 2015 BEPS Action 1 Report. In March 2017, the G20 Finance Ministers mandated the OECD, through the Inclusive Framework on BEPS, to deliver an interim report on the implications of digitalisation for taxation by April 2018. This report, Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation – Interim Report 2018 (the Interim Report) has now been agreed by the more than 110 members of the Inclusive Framework.

- The Interim Report provides an in-depth analysis of the main features frequently observed in certain highly digitalised business models and value creation in the digitalised age, as well as the potential implications for the existing international tax framework. It describes the complexities of the issues involved, the positions that different countries have in regard to these features and their implications, and which drive their approach to possible solutions. These different approaches towards a long term solution range from those countries that consider no action is needed, to those that consider there is a need for action that would take into account user contributions, through to others who consider that any changes should apply to the economy more broadly.

- Members agreed to undertake a coherent and concurrent review of the “nexus” and “profit allocation” rules -fundamental concepts relating to the allocation of taxing rights between jurisdictions and the determination of the relevant share of the multinational enterprise’s profits that will be subject to taxation in a given jurisdiction. They will work towards a consensus -based solution, noting that at present, there are divergent views on how the issue should be approached. It was agreed that the Inclusive Framework would carry out this work with the goal of producing a final report in 2020, with an update to the G20 in 2019. The Inclusive Framework’s Task Force on the Digital Economy will meet next in July 2018.

- In addition, the Interim Report discusses interim measures that some countries have indicated they would implement, believing that there is a strong imperative to act quickly. In particular, the Interim Report considers an interim measure in the form of an excise tax on the supply of certain e-services within their jurisdiction that would apply to the gross consideration paid for the supply of such e-services. There is no consensus on the need for, or merits of, interim measures, with a number of countries opposed to such measures on the basis that they will give rise to risks and adverse consequences. The Interim Report describes, however, the framework of design considerations, identified by countries in favour of introducing interim measures, which should be taken into account when considering introducing such measures.

- The Interim Report also takes stock of progress made in the implementation of the BEPS package, which is curtailing opportunities for double non-taxation. Country-level implementation of the wide-ranging BEPS package is already having an impact, with evidence emerging that some multinationals have already changed their tax arrangements to better align with their business operations. The measures are already delivering increased revenues for governments, for example over 3 billion euros in the European Union alone as a result of the implementation of the new International VAT/GST Guidelines. Also, the impact of widespread implementation of the BEPS package, including recent EU directives as well as some aspects of the US tax reform should result in neutralising the very low effective tax rates of some companies. Nonetheless, BEPS measures do not necessarily resolve the question of how rights to tax are shared between jurisdictions, which is part of the long term issue.

- Finally, the Interim Report identifies new areas of work that will be undertaken without delay. Given the availability of big data, international cooperationamong tax administrations should be enhanced, in particular, as regards the information on the users of online platforms as part of the gig and sharing economies, to ensure taxes are paid when they are due. The Forum on Tax Administration, working with the Inclusive Framework, will develop practical tools and cooperation in the area of tax administration and will also examine the tax consequences of new technologies (e.g., crypto-currencies and blockchain distributed ledger technology).

- An update on this work will be provided in 2019, as the Inclusive Framework works towards a consensus-based solution by 2020.

The European Commission does not want to wait until a global solution has been agreed for fear that current structures will manifest and more public revenue is lost, and has put forward its own proposals of how to address the issues in the long-term and in the short-term. As a first step in late 2017, the EU Commission and Council officially identified various possible avenues to make the taxation of digital activities fairer. It put forward a long-term solution, which proposes to embed the taxation of the digital economy in the general international tax framework, and a short-term solution in the interim, such as an equalisation tax on turnover of digitalised companies, a withholding tax on digital transactions or a levy on revenues generated from the provision of digital services or advertising activities. On 21 March 2018, the Commission advanced two Directive proposals, namely (1) a long-term solution to reform corporate tax rules so that profits are registered and taxed where businesses have significant interaction with users through digital channels, and (2) a short-term solution of an interim tax which covers the main digital activities that currently escape tax altogether in the EU.

The long-term solution is aimed at setting out a comprehensive solution within the existing EU corporate tax systems to tax digital activities in the EU. The proposal lays down rules to determine a taxable nexus for digital businesses operating across border in case of a non-physical commercial presence or “significant digital presence”. The concept of “significant digital presence” is meant at creating a taxable nexus in a jurisdiction where the digital business does not have any physical presence. Secondly, the proposal sets out principles for attributing profits to a digital business. These principles should better capture the value creation of digital business models which highly rely on intangible assets. As regards profit attribution, the rules will be built on the current principles for profit attribution and be based on a functional analysis of the functions performed, assets used and risks assumed by a significant digital presence. Transfer pricing rules are explicitly referred to. In determining the attributable profits, due account shall be taken of the economically significant activities performed by the significant digital presence relevant to the development, management and exploitation of intangible assets (see Infobox on the EU Proposals for further detail.)

In the short-term, the EU Commission has proposed a Digital Services Tax (DST) for adoption by EU member states. The measure is meant to prevent unilateral, non-coordinated actions by single EU member states (e.g. Italy, Slovakia, other). The DST is a 3% levy on gross revenues that would be levied alongside corporate income tax. The DST is charged annually and will also apply to domestic transactions to avoid being in breach of the provision of the freedom of providing inter-EU services. In relation to this solution proposed, there is a need to assign taxing rights. To that extend the focus is placed on user value creation: for example, in the case of sale of advertisements space, the focus will be on where the advertisement is placed; in the case of sale of data, where the user whose data are sold used a device to access a digital interface, whether during that tax period or any previous one; and in the case of availability of digital platform / marketplaces to the user, where the user uses a device in that tax period to access the digital interface and concludes an underlying transaction on that interface.

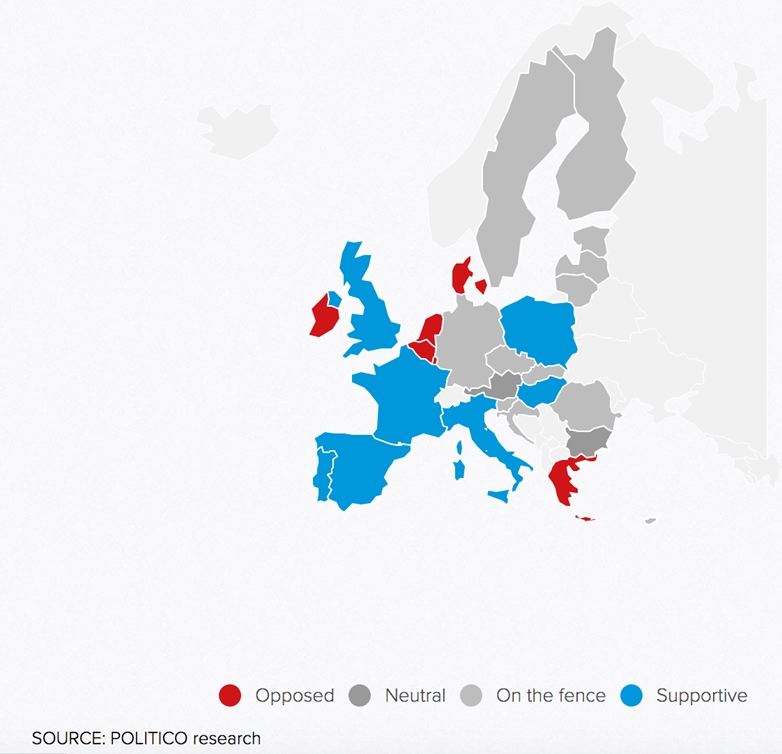

Figure 6: Where EU Member States stand regarding the EU Commission proposal

Europe is split regarding the European Commission’s proposals. While EU governments agree that tax rules should be changed to increase levies on digital services that are currently undertaxed, they want to pursue different strategies to get there. Smaller states with lower tax rates such as Luxembourg and Ireland, home to large American multinationals, want EU changes to come together with a global reform of digital taxation, which has been under discussion for years to no avail. Larger states, such as France and Italy, which claim to have lost millions of euros of tax revenue due to digital giants’ shift of taxable profits to lower-tax countries, want a quick solution and support the proposals. Figure 6 below shows where EU member states stand regarding the EU Commission’s proposal.

Austria, as the current EU’s rotating presidency holder, highlighted in a document for a meeting scheduled to take place in September 2018, that in the context of eleven of the 28 members states already considering their own national measures, reaching a uniform agreement was important so as to not undermine the EU common market. Under the current proposal, only firms with a global annual turnover of 750 million euros and EU revenue of at least 50 million euros a year would be taxable. Some 200 companies would fall within the scope of the new tax proposed by the Commission, with an estimated additional annual revenues of about 5 billion euros ($5.7 billion) at EU level. To overcome some of the criticism of the measure by the strongest opponents, Austria proposed to reduce the scope of the tax, which would no longer be applied to the sale of users’ data as in the Commission proposal. Only revenue from online advertising services (e.g. Google, Facebook), and from virtual marketplaces, such as Amazon, would be subject to the new tax, under the Austrian plan. A final decision and adoption of the EU proposal is pending, but likely to be carried over into 2019.

Spotlight: EU Commission proposal

On March 21, 2018, the European Commission presented a series of measures aimed at ensuring a fair and efficient taxation of digital businesses operating within the EU. The package includes both interim measures, in the form of a 3% Digital Services Tax on revenues, and a long-term solution, introducing the concept of a digital permanent establishment.

Introduction of a Digital Services Tax

The proposal for a Directive on the common system of a digital services tax on revenues resulting from the provision of certain digital services intends to avoid potential disparities arising within the EU as a result of the implementation of unilateral initiatives by Member States and proposes a coordinated approach to tax revenues from certain digital services.

The new Digital Services Tax (DST) would apply as of January 1, 2020, and would be levied at the single rate of 3% on gross revenues:

- The DST would apply to certain digital services, including the supply of advertising space, the making available of marketplaces that facilitate transactions directly between users, and the transmission of collected user data, while the supply of digital content or payment services, as well as trading venue and regulated crowdfunding services, would be excluded.

- Businesses that cumulatively meet certain thresholds would be subject to the DST, i.e. entities with a total annual worldwide revenue above EUR 750 million and a total annual revenue stemming from digital services in the EU above EUR 50 million. If the entity is part of a consolidated group, thresholds should be assessed at the level of the group.

- The DST should be due in the Member States where the users are located. If the users are located in different Member States, the proposal also provides for the tax base to be attributed between Member States based on certain allocation keys. The Directive also provides for cooperation between Member States in the form of a one-stop- shop mechanism, allowing taxpayers to have a single point of contact to fulfill all administrative obligations in relation to the new tax (i.e. identification, reporting, and payment). In addition, taxpayers should have the possibility to deduct the DST from their corporate income tax liability, so as to partially mitigate double taxation.

Introduction of a Digital Permanent Establishment

The proposal for a Directive laying down rules relating to the corporate taxation of a significant digital presence has a broader scope than the Digital Services Tax and is designed to introduce a taxable nexus for digital businesses operating within the EU, with no or only a limited physical presence. It also sets out principles to attribute profits to businesses having such “significant digital presence”:

- The Directive aims at taxing under the normal corporate income tax system of a Member State, profits generated by businesses providing certain digital services and having a “significant digital presence” within this Member State.

- The notion of “significant digital presence” builds on the existing permanent establishment concept and covers any digital platform such as a website or a mobile application that meets one of the following criteria: annual revenue from providing digital services in a given Member State exceeds EUR 7 million, the annual number of users of such services is above 100,000, or the annual number of online contracts concluded with users in a given Member State exceeds 3,000.

- The Directive would be applicable to EU taxpayers, as well as enterprises established in a non-EU jurisdiction with which there is no double tax treaty with the Member State where the taxpayer is identified as having a significant digital presence. However, it does not affect taxpayers established in a non-EU jurisdiction where there is a double tax treaty in force, unless such treaty includes a similar provision on digital presence.

- The proposed rules on profit allocation are mainly based on the current OECD framework applicable to permanent establishments and suggest the profit split as preferred method. Nevertheless, the Directive also details a list of economically significant activities that should be taken into account to reflect the fact that value is created where users are based and data is collected. Finally, the measures proposed by the European Commission include Recommendations to the Member States to amend their double tax treaties with third countries, so that the above rules also apply to non-EU companies. The objective of the recommendations is to address situations involving non-EU jurisdictions without violating the Member States’ existing treaties. It is expected that once a Member State applies provisions to comply with the above concept of a digital permanent establishment with respect to a country, that Member State will also cease to apply the DST with respect to that country. The proposals will now be submitted to the European Parliament for consultation and to the Council for adoption by unanimity.

The article sought to briefly examines the key features of the digitalized economy and the key issues that arise from them for taxation under current international tax rules, their repercussions at the local level, and provide a summary of what countries are doing to address the issues identified.

At the high level, the challenges brought about by the digitalized economy relate to the inability of the current international tax framework to ensure that profits are taxed where economic activities occur and where value is created. This is so because the two key concepts that the international tax framework is based on, namely the nexus rule based on physical assets and the profit allocation rule based on the arm’s length principles are outdated and do not take account of the features that a digitalized economy exhibits. These features include mobility, reliance on data, network effects, use of multi-sided business models, tendency towards monopoly or oligopoly and volatility. These new features are said to enable economic actors to operate in ways that avoid, remove, or significantly reduce, their tax liability within traditional tax bases. They may also generate base erosion and profit shifting concerns in relation to both direct and indirect taxes.

In terms of challenges for the tax policy makers, the international tax framework must be in line with domestic corporate income tax systems, which should reflect the changed way of doing business based on the new features of the digitalized economy, to avoid distortive effects at the local and global levels. To address the high-level tax challenges relating to the international tax framework, the OECD and the EU have been working to drive the development of an international solution to digital economy taxation issues, with the focus on “nexus” (namely, addressing the disconnect between tax jurisdiction and the location of value creation by expanding the definition of PE to encompass “digital presence” as determined by the location of a service’s users), and reallocating profits (namely, reallocating taxing rights among the “countries of residence”, the tax havens, and the “countries of consumption” by modifying the formulas for allocating taxable income with the users’ contribution in mind (boosting the share taxable by the countries of consumption)). While global solutions to fix the international tax system are pending, individual countries such as the UK, Australia, France, Italy, Slowakia, India, and many others are moving forward with consultations, proposals and implementation of short-term gap-stop measures, including digital services taxes, digital transaction taxes, digital platform taxes, equalization levies and changes to concepts of permanent physical establishment.

In summary, taxation should manage the interests of stakeholders at the domestic but also at the global level, and its effect should be neutral across different sectors of the economy and countries. The advent of the digitalized economy exacerbates issues, some of which were already present with global activities of MNEs prior to the extent of digitalization that we face today. This is currently not reflected in the international tax framework. It is therefore important that countries continue the dialogue and jointly identify solutions to adjusting the international tax framework to reflect technological and economic advancement and societal development and thereby minimize global asymmetries and local distortions.